Give it Away

Most consumers care about their personal data privacy but don’t know how to: a) take back their data, and b) monetize their data. Not only are governments stepping up regulations to protect consumers, but awareness around the value of personal data is starting to proliferate across the media. As consumers realize the value of their personal data, they may be inclined to protect it and find a way to monetize it. And they may realize that they have zero visibility on who has what of yours, and how they are using it.

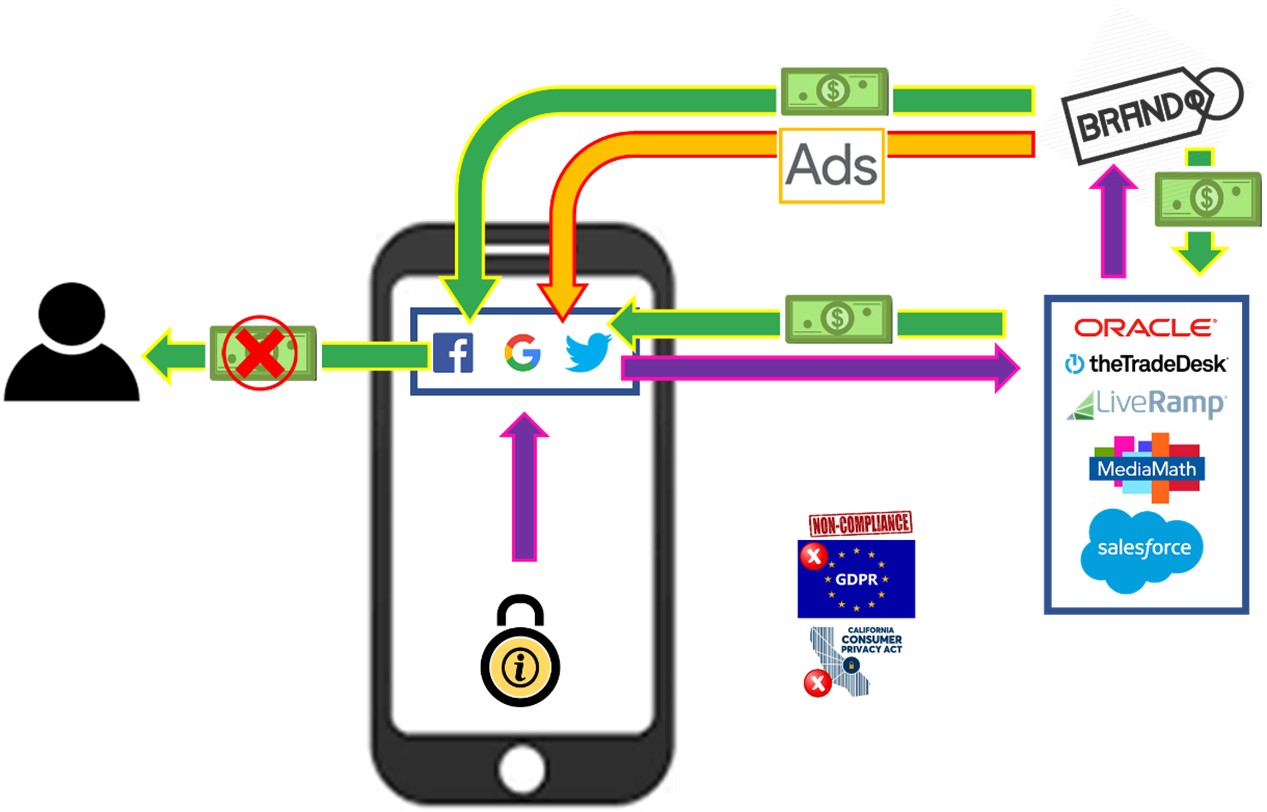

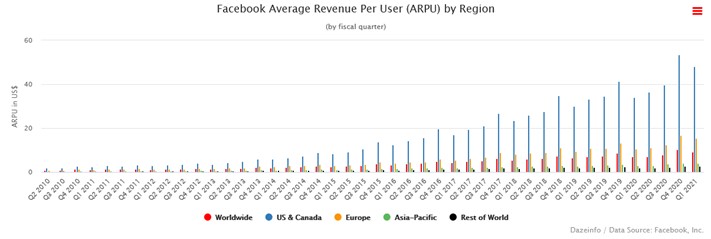

Here is what happens when we use social media, applications, and websites. In exchange for free access, we provide (often voluntarily) details about who we are, what we do, where we are, our interests, apps we use, Internet pages we visit, who our friends are, and much more. Companies create a profile about you from your personal data, which is then packaged by companies like Oracle and sold to brands and data companies. The providers of personal data collect fees for selling your info (Facebook made about US$48 million on Americans and Canadians in Q1F21). Even the largest social media companies use third-party data to enhance their profile about you because you are not only a user and promoter of their platforms, but you are also their product.

Brands and websites monetize your data while you get squat (except for annoying ads).

Source: Dazeinfo

Social media, apps, and websites monetize your personal data, and you get squat. Worse, we know that many of the largest companies aren’t good stewards of our personal information. Your data is circulating around the Internet and stored in data centers waiting to be hacked, the consequences of which can be devastating as this man discovered years ago.

Source: Gulf News

Consumer Privacy is Paramount

Data breaches are a regular occurrence. The March 2020 attack on adult website Cam4 exposed 10.88 billion records that included subscriber names, email addresses, chat logs, and payment logs. And a year later, data breaches have not subsided: a January 2021 data breach at Chinese social media company Sociallarks.com exposed 200 million records; clothing store Bonobos saw 12.3 million records breached in January 2021; also in January 2021, a breach dating app MeetMindful affected 2.28 million users. Perhaps the Facebook breach in April 2019 that affected 533 million users in 106 countries was the most prominent in the media, especially after all the data was leaked for free. You can read Facebook’s response HERE.

Well before these data breaches occurred, some governments took action to hold enterprises responsible to not only safeguard consumer data but also require consent to collect, amalgamate, and monetize personal data. The European Union implemented General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) in May 2018 to protect the data and privacy of citizens. Organizations, both European and non-European, breaching GDPR can be fined up to the greater of 4% of annual global turnover or €20 million. A company can be fined 2% for not having their records in order, not notifying the supervising authority and data subject within 72 hours of a breach, or not conducting impact assessments. Okay – these fines aren’t onerous for larger non-compliant firms, leading us to believe that the bigger reason for GDPR is to inform consumers about how companies are collecting, amalgamating, and monetizing their personal data.

Although the United States doesn’t have a comprehensive national law like GDPR that regulates the collection and use of personal data, the Data Care Act of 2018 sought to protect personal information online and penalize companies that fail to safeguard the data. However, it was never acted upon by the Committee tasked to study the Act. However, Senator Brian Schatz from Hawaii reintroduced the bill on March 23, 2021 and proposes that the Federal Trade Commission the enforcement authority.

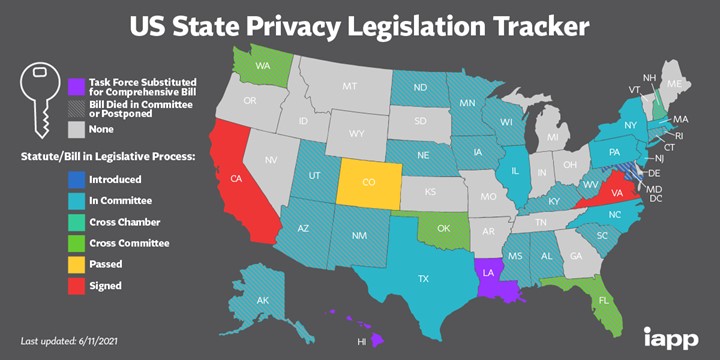

In parallel, Representative Suzan DelBene from Washington reintroduced the Information Privacy and Data Transparency Act that would adapt state privacy laws and proposals into a national standard for data privacy. The lack of U.S. national data privacy laws did not prevent states from implementing their own laws. On January 1, 2020, California took the lead with its California Consumer Privacy Act, (“CCPA”), giving consumers new privacy rights to control their personal information. Virginia passed its Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (“VCDPA”), scheduled to go live January 1, 2023. Colorado passed its Colorado Privacy Act on June 8, 2021 and takes effect in July 2023. And as Exhibit 1 shows, most U.S. states are in the process of establishing data privacy laws (Exhibit 1). However, most bills have failed in committees (the initial stages) and will likely be reintroduced, similar to what happened in Virginia and Colorado. But the key takeaway is that consumer data privacy is top-of-mind for U.S. politicians.

Exhibit 1: The majority of U.S. states are actively looking to pass data privacy laws

Canadian lawmakers also want to strengthen consumer privacy laws. The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (“PIPEDA”) sets the rules for how private-sector organizations collect, use, and disclose personal information in the course of for-profit, commercial activities across Canada. However, Bill C-11, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2020, would repeal parts of PIPEDA and replace them with a new laws governing the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information for commercial activity in Canada. The Bill would enhance the role of Canada’s Privacy Commissioner in overseeing business compliance.

Businesses at Risk

Many business models are dependent upon the collection, amalgamation, and monetization of our personal data, so businesses – including the largest tech enterprises – are concerned. Their main data inputs are at risk, and our next report will explain why.